Theological Triage and Historical Precedent

In 2005, Albert Mohler introduced the term “theological triage” in his article, A Call for Theological Triage and Christian Maturity. He drew an analogy from the medical field, where emergency responders prioritize patients based on the severity of their condition. Similarly, theological triage helps Christians distinguish between doctrines of first-order importance (the Gospel itself), second-order importance (denominational distinctions), and third-order importance (matters of Christian liberty and conscience). This framework is helpful in navigating theological disagreements without either compromising truth or unnecessarily dividing over lesser issues.

Though Mohler coined the phrase, the concept is far from new. Many theologians throughout church history have recognized the necessity of distinguishing between doctrines of different weight. Francis Turretin (1679–1685), in Institutes of Elenctic Theology, categorized doctrines as either fundamental (essential for salvation) or non-fundamental (important but not essential). Similarly, the Westminster Confession of Faith (1647) and the Second London Baptist Confession (1689) both imply theological triage by distinguishing between matters essential to salvation and those necessary for church order and practice—such as church government and the sacraments.

Other theologians1Like Kevin DeYoung, Andy Naselli and Gavin Ortlund have expanded upon Mohler’s modern framework, providing additional nuance to the discussion. However, the heart of theological triage remains a biblical principle: Christians must learn to discern which doctrines require absolute commitment (Jude 3), which require strong conviction (Romans 14:5), and which allow for charity in disagreement (Romans 14:1-4).

I will attempt to build upon this framework, outlining a hierarchical approach to theological disagreement when it comes to recommending books, persons and theological camps. By categorizing differences into first-order (Gospel-defining), second-order (denominational), and third-order (Christian liberty) issues, we can engage theological differences with both faithfulness to Scripture and a spirit of unity (Ephesians 4:13-15). I will add a tier in between first and second order issues that I have found helpful especially when conscientiously endorsing an author or work that may require a gentle warning.

A Hierarchical Approach

Theological disagreements are inevitable within the Church. However, not all disagreements carry the same weight or have the same implications for faith and practice. Some differences strike at the very core of the Gospel, while others are secondary or even tertiary in importance. Recognizing these distinctions is crucial for discernment in both personal faith and the broader ecclesiastical context.

1. Disagreements on First-Order Issues: The Core of the Gospel

Paul speaks of “matters of first importance” in 1 Corinthians 15:3-4, emphasizing Christ’s death for our sins, His burial, and His resurrection as the foundation of the Gospel. First-order issues are those that define Christian orthodoxy. They include:

- The deity of Christ (John 1:1; Colossians 2:9).

- Salvation by grace through faith alone (Ephesians 2:8-9).

- The bodily resurrection of Christ (Romans 10:9).

- The authority of Scripture (2 Timothy 3:16-17).

To deny these essential truths is to reject the Gospel itself. This is why John warns in 1 John 2:22 that anyone who denies Christ is “the antichrist.” Such denial is not merely error—it is heresy in its most serious form. False teachers who distort these doctrines are described in Galatians 1:8-9 as those who preach “another gospel,” and Paul says they are accursed.

If an individual or group denies a first-order doctrine, they fall outside the bounds of Christianity, regardless of their claims to the name of Christ. Thus, if recommending a book by a Mormon author—who may write well on parenting or leadership—it would still be necessary to warn that Mormonism denies core Gospel truths such as the full deity of Christ and justification by faith alone.

2. Disagreements on Issues Closely Connected to the Gospel

Some theological errors do not explicitly deny the Gospel but dangerously undermine it. These errors, if taken to their logical conclusion, would lead to a different Gospel. Examples include:

- Denial of sola Scriptura (2 Peter 1:19-21).

- Denial of biblical inerrancy (Psalm 12:6; John 17:17).

- Corruptions of justification by faith alone, such as Federal Vision theology, which blurs the distinction between faith and works (Romans 4:5).

These views often still claim to uphold the Gospel, but their errors place the truth in jeopardy. Many adherents may remain inconsistent, affirming salvation by grace while simultaneously holding doctrines that, if followed consistently, would undermine it.

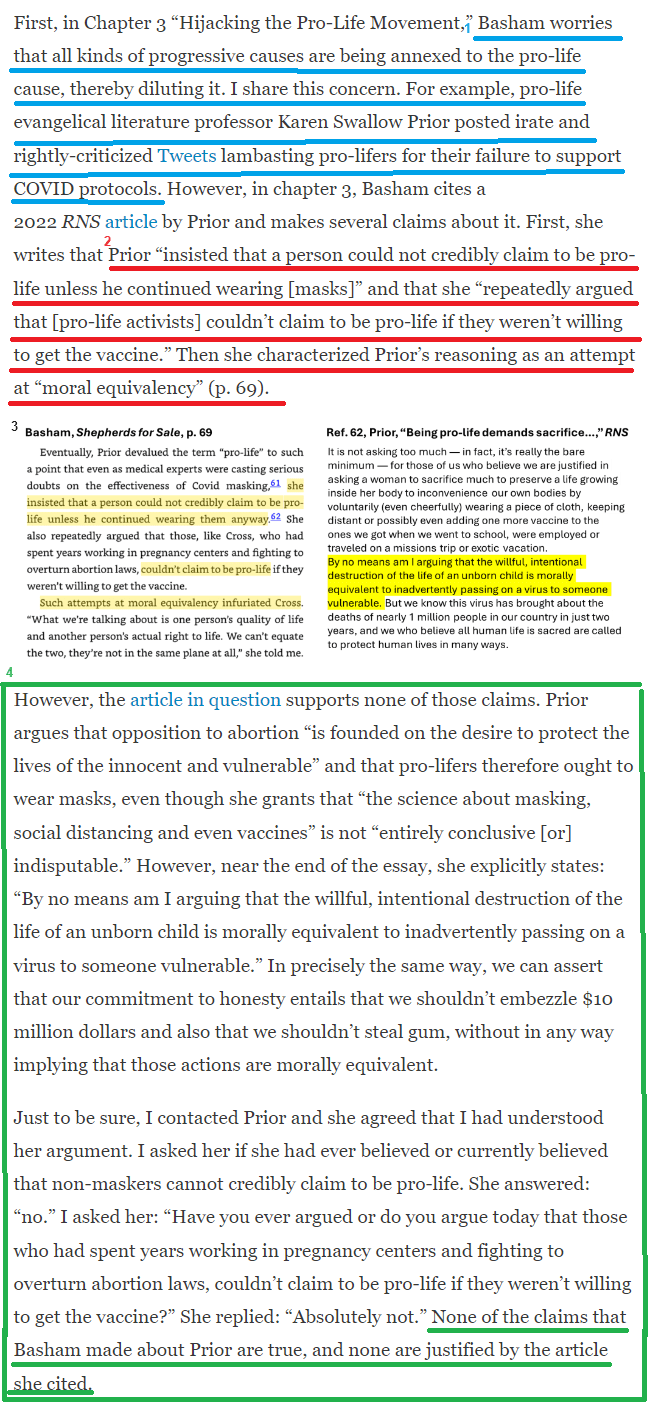

Because these errors threaten Gospel clarity, they require caution when engaging with teachers who propagate them. For instance, John Piper’s view of “final justification” could be problematic if taken to its logical end, as it potentially confuses the finished work of Christ with future performance. While Piper is a faithful brother in many respects, a responsible recommendation of his work should acknowledge this concern. Likewise, a scholar like Bruce Metzger may offer valuable contributions in textual criticism, but his denial of biblical inerrancy requires a cautionary note.

3. Disagreements on Second-Order Issues

Second-order issues are significant theological disagreements that affect church practice but do not define orthodoxy. These issues often lead to denominational distinctions because they impact the structure and function of the local church.

One of the clearest examples is baptism:

- Paedobaptists (Presbyterians, Reformed) argue for infant baptism based on covenant theology (Genesis 17:7; Acts 2:39).

- Credobaptists (Baptists) argue that baptism should be reserved for professing believers (Matthew 28:19-20; Acts 8:36-38).

A local church must take a stance on baptism, and cannot consistently practice both views. However, both positions have been held by faithful believers throughout church history.

Female Pastors and Elders

The question of female pastors, teachers, and elders is another issue that falls within this category, and helps to illustrate how disagreement on a Second-order issue can vary in complexity and severity.

- If the issue is framed merely as an internal debate about church governance and roles, it remains a second-order issue—one that significantly impacts church structure but does not outright deny the Gospel. Complementarians (who hold to male-only eldership) and egalitarians (who affirm female pastors/elders) may disagree strongly, but there are egalitarians who still affirm the core truths of the Gospel and the authority of Scripture.

- However, depending on the degree to which the issue is expanded upon, it can also fall under issues closely connected to the Gospel (category #2). This is particularly the case when:

- The argument for female pastors/elders denies or reinterprets biblical authority (1 Timothy 2:12; 1 Corinthians 14:34-35).

- The reasoning used to justify female ordination extends to redefining gender roles in a way that undermines biblical anthropology (Genesis 1:27; Ephesians 5:22-33).

- The issue is tied to broader cultural pressures that reject biblical teachings on sexuality and gender, leading to a slippery slope into theological liberalism (which is heretical).

Because second-order issues are not Gospel-denying in themselves, endorsing the work of a believer who differs on a matter like baptism or church governance is more straightforward. However, if an author promotes a position like egalitarianism, in a way that undermines biblical authority, the concern moves beyond mere disagreement and requires a more serious warning.

4. Disagreements on Third-Order Issues: Matters of Christian Liberty

The vast majority of disagreements within the Church fall into this category. These are issues of personal conviction where Scripture allows for differences of conscience. The list of examples is seemingly infinite:

- Is it ok for Christians to watch Mixed Martial Arts? How about NFL Football?

- Is it ok for Christians to hunt for sport? How about if they eat their prey afterwards? Only if they NEED the animal for food?

- How should Christians educate their children? Public school ok? Private school? Homeschool?

- Is it ok for a Christian to work for MLM? How about a credit card company? Or Frito Lay? Or a progressive company like starbucks who supports Planned Parenthood?

- For that matter is it ok to DO BUSINESS with companies who support things like Planned Parenthood at all? Like, can you even shop at Target???

- Is it ok for Christians to eat fast foods? Does I make it ok, if it’s Christian Fast Food? (Chick-Fil-a)

- Ok for men and women to swim together? Only if they wear a t-shirt over their bathing suit? Only in a one-piece? Is a two-piece ok?

- Can a Christian serve in the military? As a police officer? How about to elected office?

- Can Christians read or watch Harry Potter? Disney? What if it’s Christian Disney? (Lion The Witch and the wardrobe?

- Can a Christian vote for Donald Trump? How about Bernie Sanders or Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez? Ok for a Christian to either NOT vote or vote for a Christian politician who in all likelihood can’t win?

These issues fall under the Reformed doctrine of Christian Liberty (Romans 14:5-6; 1 Corinthians 10:23). The danger here is two-fold:

- Legalism – where someone elevates a personal conviction to a universal law, binding others’ consciences where Scripture does not. This imposes extra-biblical requirements on believers, leading to unnecessary division and burdens not commanded by God (Colossians 2:16-17; Matthew 23:4). Legalists create man-made tests of purity for both themselves and those around them, condemning others as disobedient for failing to follow rules that, while not contrary to Scripture, are not explicitly commanded in Scripture (Mark 7:6-7).

- Antinomianism – where a person insists that something is not sin, even when Scripture provides ample evidence that it could be sin depending on the context. This leads to a reckless dismissal of biblical wisdom (Galatians 5:13; Romans 6:1-2). Christian liberty is meant to help us choose how best to obey God’s Word, not excuse ourselves from obedience altogether.

The Doctrine of Christian Liberty doesn’t exempt Christians from obedience to God’s law, rather it frees the Christian to pursue obedience with a clear conscience when well meaning Christians disagree on the best way to obey God. We do well when we bind our own and our brother’s conscience to what the bible binds him to, but we presume to speak for God when we erect our own rules as if they were God’s revealed will for all Christians (and we risk violating the 3rd Commandment when we do).

The Challenge of Endorsements and Warnings

In my experience, third-order issues pose a difficult challenge when deciding whether to endorse a theologian, book, or institution. While these matters fall under Christian liberty, some teachers and thinkers fixate on them to an unhealthy degree, risking the distortion of Christian priorities. When evaluating a potential endorsement, one must consider: Is this third-order issue seemingly all they talk about? If someone continually harps on a non-essential topic, making it the centerpiece of their public ministry, they risk turning a molehill into a mountain—confusing a matter of Christian liberty with a test of pure faith. Similarly, one must ask: Does their language or demeanor give the impression that they view this as a first-order issue? Some hold third-tier positions with such intensity that they bind consciences as though their preference were a divine mandate (Mark 7:8-9). For example, it is one thing to believe that homeschooling is the best method of Christian education, but quite another to suggest that those who send their children to public school are failing as believers. Finally, are they charitable toward those with differing views, or do they demean and belittle their opposition? (Ephesians 4:29). A theologian’s tone, posture, and approach often reveal whether they truly recognize an issue as third-tier or whether they have subtly elevated it to a test of faithfulness.

Because these dangers are real, discernment is necessary when endorsing books, ministries, or theologians. Christian liberty should be handled in ways that communicate clarity, honesty, humility, and grace—never with legalism or dismissive arrogance. While it is appropriate to hold strong convictions on third-order matters, we must always be mindful of what Scripture binds us to, neither imposing unnecessary burdens nor casting off wisdom under the guise of freedom (Romans 14:19).

Perhaps less common, but far more dangerous, are issues that, while not strictly first-order, are so closely connected to the Gospel that they threaten its integrity. The danger often lies in how these issues are presented. When theologians are forthright about their views and clearly distinguish their position from historically held orthodoxy, it becomes easier to assess their work and responsibly engage with it. But far too often, this is not the case. Many theologians and authors cloak their departures from historic teaching in familiar, orthodox-sounding language, subtly redefining key doctrines while avoiding full transparency. Pastors and elders must exercise vigilance, carefully discerning whether such figures are speaking in a way that aligns with biblical truth or introducing novel reinterpretations under the guise of tradition. The stakes are nothing less than the hearts and minds of God’s people—those whom He has entrusted to the care of shepherds, and for whom they will one day give an account (Hebrews 13:17).